The ICE Occupation of Minneapolis: They Call It ‘Security.’ The Pictures Say ‘War.’

As Trump sells ‘law and order,’ most of politics and media still treat ‘war’ as a metaphor. On the ground, photographers see it and show it for what it is.

A federal agent is firing tear gas into a crowd. The visual grammar is combat: obscured sightlines, tactical aggression in urban terrain, and chemical weapons deployed against civilians. The fog—literal and figurative—shrouds what’s happening in the language of war. You could be looking at Gaza, Fallujah, or any number of conflict zones. Except this is Minneapolis.

The term “war,” as applied to the mission of Trump’s Homeland Security agency, remains overwhelmingly understood by politicians and journalists alike as hyperbole, as metaphor. Just like people mocked or shrugged when the Pentagon renamed itself “the Department of War.” But the depictions from Minnesota express exactly what the semantics indicate: in language, verbal as well as visual, it is what it says.

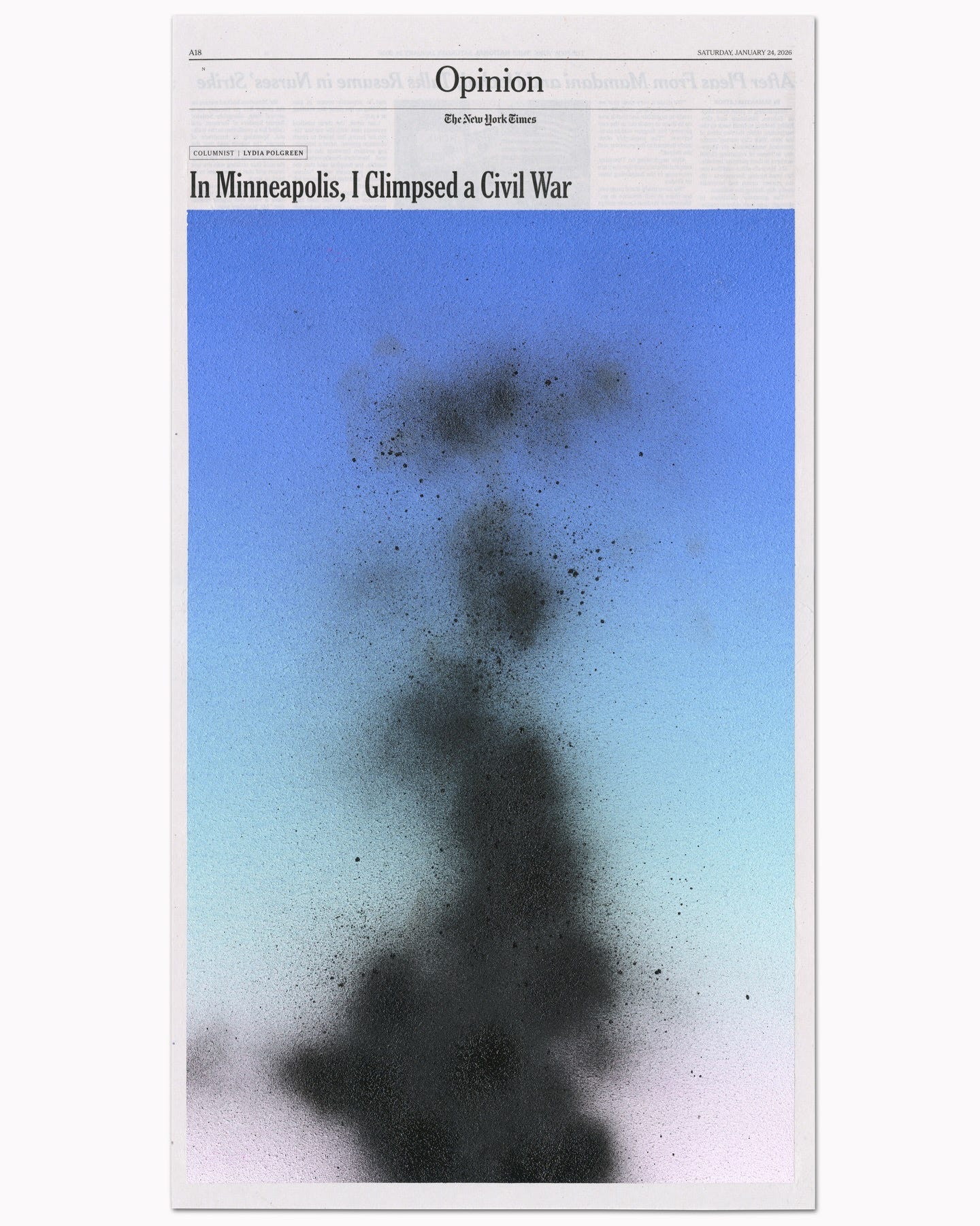

The artists Shoshibuya gets it. His latest interpretation of a New York Times Opinion page not only captures the smoke from the attack on Minneapolis, the blotches of paint like shrapnel, but he “publishes” the words the media, like The Times, will not use.

Not just a war, but a civil war.

This gray, primal photo by David Butow primes the comparison.

The composition of civilians watching federal forces at a fortified position, with the flag as the focal point, evokes the April 12-13, 1861, attack on Fort Sumter. The flag held by protesters facing federal agents marks the same contested sovereignty. That residents in Charleston expected a show echoes the same underestimation. Then as now—with the future of democracy on the line in Trump’s purge of immigration and First Amendment rights —‘war’ isn’t a flourish or a figure of speech. That’s what the pictures show.

Ultimately, the sight of federal agents armed to the teeth says everything before anyone moves. This isn’t crowd control. It’s insurgency.

The Fronts

War doesn’t move in a straight line. In Minneapolis, it’s advancing on at least three fronts.

The Civic Front

Most images from Minneapolis catch isolated incidents—a single raid, a single clash with protesters, a single breached doorway. Phones record what’s right in front of them. This one does something else: it shows scale.

That’s why Tim Evans’ photograph traveled so widely. It’s one of the few pictures that makes visible what people only hold in their heads: this isn’t discrete law enforcement. It’s sustained territorial operations. Once you lock onto that, the burning columns stop reading as just a few fires; they become location markers, cries, and statements of resistance all at once.

The Removal Front

Philip Montgomery’s photograph captures an ambient terror spreading far beyond the streets where the agents actually operate. A person stands at the window, caught between private and public, safety and threat. Her gaze aligns with the camera, not on any federal presence off‑frame.

The window frame matters. In war photography, windows and doors often mark vulnerability—the moment before breach, the boundary that won’t hold. Montgomery places the figure squarely inside that frame, making the psychological operation legible even when no agents appear in the shot.

This is what systematic removal looks like at the domestic scale: uncertainty as a weapon. You don’t know when they’re coming. You don’t know if you’re next. The terror runs 24/7, even when enforcement is sporadic. That’s the design.

The assault on Teyana Gibson Brown’s home is tactically identical to home invasions I documented during U.S. raids in Fallujah in 2004 and 2005: door-breaching, tactical stacks, overwhelming force against civilian residences. A New York Times video breaks down the equipment—silencers, MAWLs, M-LOKs—gear militarized since the Gulf War, standard SWAT issue, now deployed for immigration enforcement.

But the precise historical parallel comes from wars explicitly understood as systematic removal operations: Bosnia, Kosovo, Rwanda. In Bosnia (1992-1995), Serbian forces carried out house-to-house operations, forced displacement, terrorizing families. In Kosovo (1999), a centrally organized campaign to clear regions of ethnic Albanians.” In Rwanda (1994), door-to-door searches created pervasive fear.

What’s happening in Minneapolis fits this pattern. Sporadic raids, battering rams at dawn, the uncertainty of who is next—systematic removal carried out as a police operation, incident by incident, house by house.

The Press Front

Photographers aren’t documenting this war from the sidelines—they’re targets. John Abernathy’s camera is mid-flight as federal agents tackle him, in a frame Pierre Lavie shot to preserve his images. Lavie later described reaching for Abernathy’s phone as a federal officer repeatedly tried to stomp on it—”I had to Hungry Hippo my hand in and out to avoid my hand getting stepped on,” he said.

The pattern is systematic: Jon Farina shot with crowd-control munitions; Zach Roberts struck in the head; Nick Valenciatear-gassed and shoved—all wearing press credentials. You can’t assault every citizen with a camera. But you can send a message by assaulting those who represent the fourth estate.

Photos Deeper Than the Denial

Photojournalists are not just recording the rituals of battle. In a highly charged, increasingly authoritarian political climate, they are tuned to the atmosphere around those rituals—the nuances, ironies, and visual echoes of other wars that emerge from contested narratives and propaganda. Their photographs register not only the clashes themselves but also the ways in which a society is gaslit into thinking it’s no war at all.

Given the circumstances, the many conflict- and terror-associated connotations in Mostafa Bassim’s image are not unreasonable. They converge in a single phrase: the fog of war. The shroud of the gas and the body language of the citizen at the far right remind me of Lower Manhattan during the fall of the World Trade Center. In the street, the trees, and the body language, a few might even see hints of The Napalm Girl. At the same time, the fog itself reflects the ambiguity of language—the way it obscures any attempt to call the siege in Minnesota exactly what it is.

The canister suspended in the air—mid‑arc, mid‑detonation. The documentary distance lets us study the moment almost clinically. That clarity cuts against the chaos the violence intends. The shock and awe, the ‘flooding the zone,’ are designed to traumatize—to make thinking impossible. The freeze-frame, instead, lets us process the fireworks rather than absorb their impact. It’s a portrait that says to Trump, Miller, and Noem: we get what you’re about.

Talk about a photo that goes the other way. The vulnerability in this agent’s body. The fear in his eyes. The sheerness of the mask, more like lingerie. Where the troops are largely untrained, barely managed, and operating with little plan, many of them are simply scared to death. Undermining the sense that Trump’s enforcers are all attack dogs and soldier‑of‑fortune types, this image captures a deeper truth: they—like the citizens hunted at their car doors—are equally caught in the crossfire.

Thank you for visiting Reading the Pictures. Despite our visually saturated culture, we remain one of the few sources for analyzing news photography and media images. This post is public, so feel free to share it.

To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. As a non-profit organization, your subscription is tax-deductible.

thank you so much for this. you have said it ALL. I’m a retired photo-editor; of course one never retires. Your spotlight and analysis is much needed. Bravo to all.

A great, and very sharply pointed, set of images and analyses.

However, if the report in ProPublica of the names of two of the agents who killed Alex Pretti got it right, both were experienced (as was Ross, who killed Renee Good). Both were border control agents of one sort or another. One wonder what other illicit and brutal actions they've carried out with impunity in their previous roles, away from scrutiny, kinda like the old timey Texas Rangers. Their presumptive ethnic identities also raise a host of questions.